Introduction

Many of us find digital technologies inescapable in our personal and professional lives, as a mobile phone and email account are necessary for most people in the workforce. Even for people who have not been affected by FDV, the expectation to keep on top of constant notifications from our computers, tablets and phones is exhausting.

The use of technological devices to harass and stalk FDV victims has been a topic of discussion for decades, and it is only becoming more relevant; although it predates the release of smartphones by nearly a decade, the Surveillance Devices Act (WA) was proposed in 1998 to “regulate the use of listening devices in respect of private conversations, optical surveillance devices in respect of private activities, and tracking devices in respect of the location of persons and objects”.

A pattern of behaviours utilising technology as a means of abuse or coercion is often defined as technology-facilitated coercive control, tech-abuse or technology-faciliated abuse (TFA). This is often used in conjunction with other abusive behaviours, such as physical abuse and financial abuse.

There has been a concentrated effort to better understand the use of technology in FDV cases, as the “National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032” (Department of Social Services 2022) lists TFA under the definition of coercive control. The Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence, based in New York, defines TFA as “A pattern of behaviour and coercive tactics perpetrated against an intimate partner with the goal of establishing and maintaining power and control through the misuse or manipulation of technology”

Signs

If someone were engaging in TFA against you, you might notice of the following signs:

- The perpetrator might appear where you are, or things you’ve said in messages not shared with them.

- Your phone battery drains very quickly.

- You notice fake profiles following you on social media.

- You get notifications that someone has tried to log in to your account (email, social media, online banking).

- You may notice text messages or emails on your account being sent, deleted or read but not by you.

- Assistive technologies in your house may be operating strangely, or changed to uncomfortable settings, not by you.

Methods

Stalkerware

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Study in 2023, 1 in 5 (20%) women and 1 in 15 (6.8%) men have experienced stalking, since the age of 15 (ABS 2023). Before smartphones, stalkers often physically following the victim-survivor around, monitored the victim-survivor’s address, and sent intimidating letters or made threatening phone calls. With the use of technology, stalkers can monitor the victim-survivor’s location in real time from their phone with geo-tracking apps, and harass them via text, email and phone call.

Some stalkerware apps, often marketed as productivity trackers for employees or location trackers for worried parents, can be far more invasive. Some apps record keystrokes, call logs, search and browser history and data from messaging app. One app even allows users to record phone calls and surroundings using the microphone. If a victim-survivor were organising to escape from an FDV relationship, the perpetrator may be able to access the details of their plans from messages, or even from writing it down in their notes app – making it even more dangerous to attempt to leave.

Internet of Things

Modern connectivity provides a lot of convenience in the modern world: using designated apps, you can set your washing machine to finish just as you get home, monitor your heart rate and sleep quality before a doctor’s appointment with fitness trackers, and dim the lights to your liking with smart lightbulbs. But when this technology is harnessed by an abuser in an FDV case, it can turn your safe place into another monitored zone.

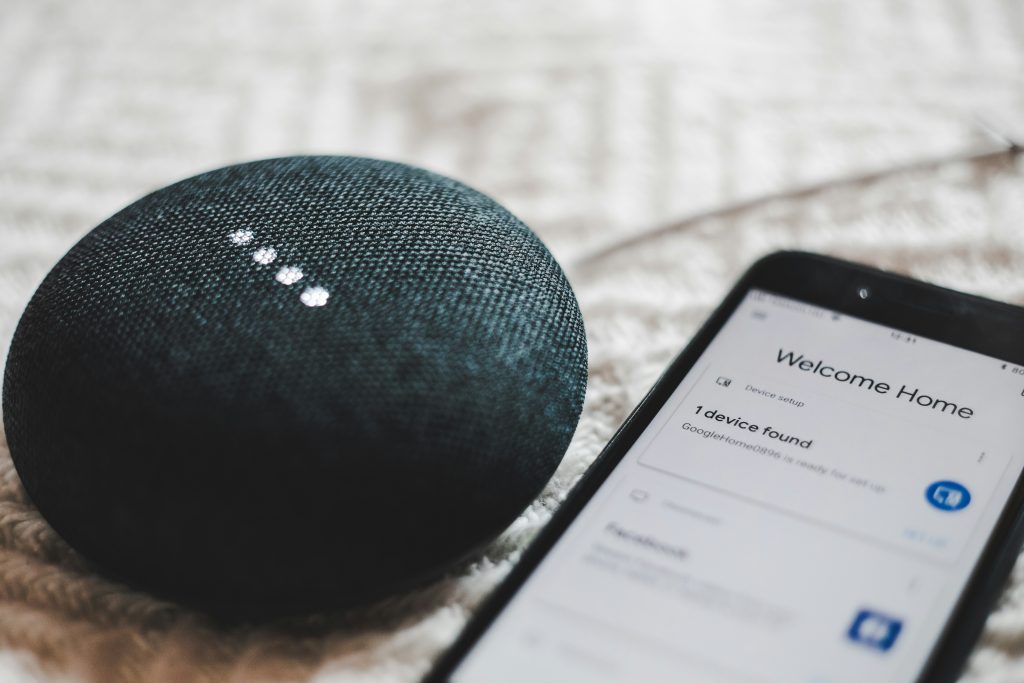

In absence or after separation in FDV cases, the perpetrator may make the victim-survivor’s living space uncomfortable or disrupt their sleep by changing the thermostat settings remotely. Voice assistants such as Siri or Google Home can be used to monitor private conversations, send threatening messages or indicate control over things like light settings or devices.

In particularly threatening situations, digital locks can be accessed to lock the victim-survivor inside the house, or lock them out. Security cameras, often set up as a protection method in FDV cases, can also be used as monitoring devices

Image-based abuse and sextortion

In the “National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032” (Department of Social Services 2022), the report states “We have also seen an increase in sexual violence in all settings, including online, and perpetrators using new mechanisms, including violence facilitated by technology”. With the increased accessibility of open-source artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, this problem will become more common and more complex.

Perpetrators of FDV may threaten to release intimate photos and videos in order to maintain control over the victim-survivor. These photos and videos may be taken and obtained with consent during the relationship, but the victim-survivor may face social and cultural stigma and shame if they were to be shared to their family; it may also result in the termination of their employment if shared to their workplace or uploaded to adult entertainment websites. This is an offence now known as revenge-porn.

Even for victim-survivors who feel confident that they have never been photographed or videoed by their partner, the risk of image-based abuse is still relevant. With deepfake technology, the perpetrator can generate a realistic image or video of the victim-survivor by uploading photos and videos to AI software. From the eSafety Commissioner, Deepfakes have been used to create and share fake news stories, pornographic videos of celebrities and malicious hoaxes.

What To Do If You’re Experiencing TFA

Stay Calm

If you suspect someone is engaging in TFA against you, it is important to keep calm, as the perpetrator is trying to intimidate you.

Gather Evidence

Collect screenshots of call logs, abusive text messages, log-in attempts, voice messages, emails or threats. Note any instances of home technology interference, such as flickering lights, threatening voice messages or locked doors you didn’t activate.

Call the Police

If you are in Australia and in immediate danger or at risk of harm, call emergency services on Triple Zero (000). Contact your local police on 131 444 if there are threats to your safety or threats to your friends or family members.

Change Your Privacy Settings

You can turn off the location of your device, and restrict access to GPS data. You can also change your privacy settings on your social media profiles, following Women Who Code’s guide here.

Don’t Delete Messages or Stalkerware Apps

If your location is being monitored or you find stalkerware software installed on your device, it is not recommended that you delete the stalkerware until you talk to police. This is because deleting the app can erase the records of the harassment, and it may let the perpetrator know that you’ve become aware that they’re tracking you.

Stay Cautious

If you’re not sure who would have a motive or ability to perpetrate TFA against you, the eSafety Commissioner recommends you be wary of anyone trying to “rescue” you.

“You are being threatened or receiving unwanted contact and someone steps in to offer advice and support, but they seem to know a lot about what is going on. Their intention is to separate you from your social circles, so they can come to ‘rescue’ you, making you grateful and trusting even though they are secretly the one who caused the problem.”